Warning: The following contains spoilers for Jujutsu Kaisen, Episode 51, “Perfect Preparation”, now streaming on Crunchyroll.

Late last year, I wrote about Gachiakuta and how refreshing it felt as an anime-only to go into a new series from my favorite studio with the manga’s first three volumes fresh in my memory. It felt cool to experience what manga readers must go through every time a new adaptation comes out, and judging its early episodes with some added context/authority offered some nuance to my time with it that I wasn’t used to. Now, unfortunately, the anime quickly outpaced what I was able to read in the manga, mostly because no bookstore around me had Volume 4 for some reason. Thankfully, just a few months later, I would be subject to an even greater catharsis as Jujutsu Kaisen: The Culling Game Part 1 began airing.

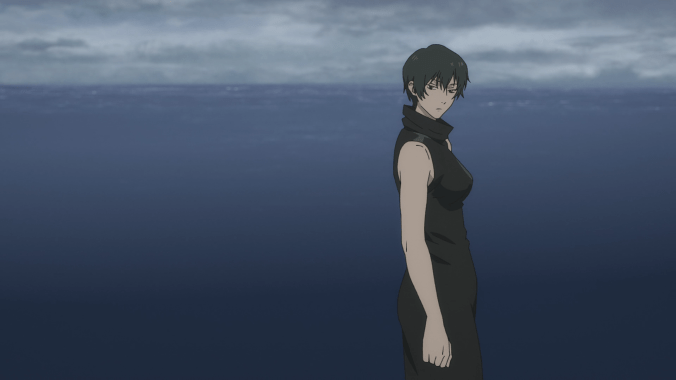

With Gachiakuta, it was something new to me, and whether I was reading it or watching it, I hadn’t fully decided if I liked it or not yet. With Jujutsu Kaisen, on the other hand, I had already read the manga to completion last year while waiting for the show to return, which was certainly an experience to say the least. And for all the insane battles, cool characters (both wasted and not), and the at-times cumbersome culmination of the series intricate magic system, there was really only one arc that I was desperately hungry for above all the others… The Perfect Preparation Arc. In other words, the moment Maki became the coolest character.

A Crash Course In Loving Maki Zenin

Ever since Season 1, Maki Zenin has been one of my favorite members of the cast. It’s easy to root for underdogs, but I’m especially a big fan of characters who are veritable powerhouses despite their handicaps. In Maki’s case, she was born with a heavenly restriction that gave her barely any cursed energy, much less the ability to see cursed spirits. As a child of the Zenin clan, one of the “Big Three Families” of jujutsu sorcery, she is a pariah. She should be one of the weakest characters in the story. Except heavenly restrictions always come with a flipside, and hers was that she was born with superhuman strength to compensate.

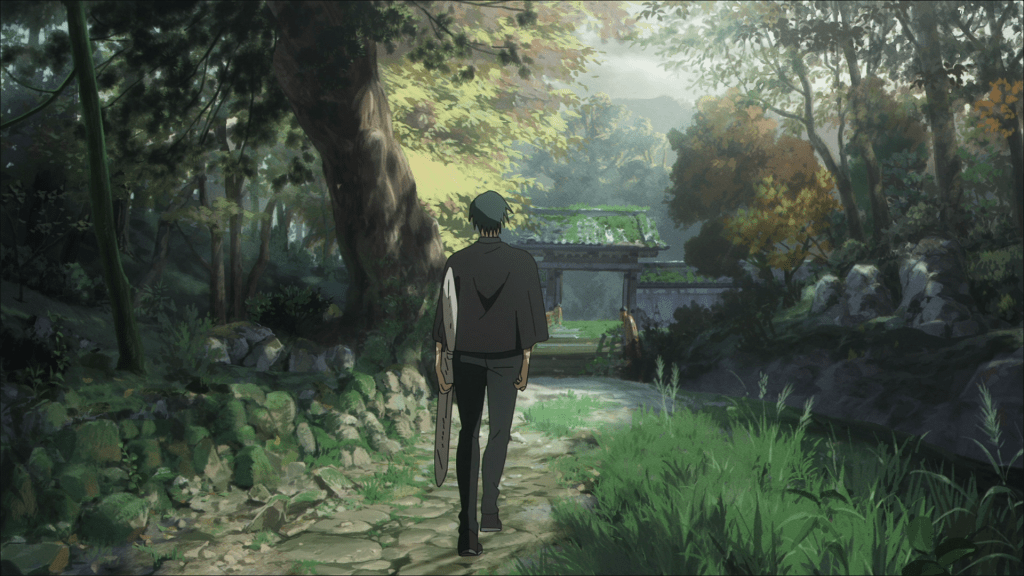

So, with a special pair of glasses that let her see cursed spirits and an arsenal of cursed tools to slay them (that she has made herself frighteningly proficient with), the barriers between her and a successful career are considerably reduced. The audience’s first impression of her, be it in Season 1 or the film Jujutsu Kaisen 0, is not only that of an upperclassman, but a complete badass in a way all her own, and she only got cooler the more we became privy to her past. She’s awesome, but she’s also really inspiring to others like Nobara because of what she’s overcome and the confidence she exhibits in the face of adversity.

My favorite episode of Season 1 was Episode 17, which was fittingly directed by Shota Goshozono, the man who directed Season 2 and who is currently at the helm of Season 3. It’s one of my favorite anime episodes because, in addition to being a frenetic, action-packed chapter in an already exciting arc, it is wonderfully written, notably in how it examines the women of this series. I wrote a piece about this back in 2023 for anyone eager for a more extensive refresher, but among other things, this was the moment that I – and I presume many others – started to resonate with Maki.

The Family We Love To Hate

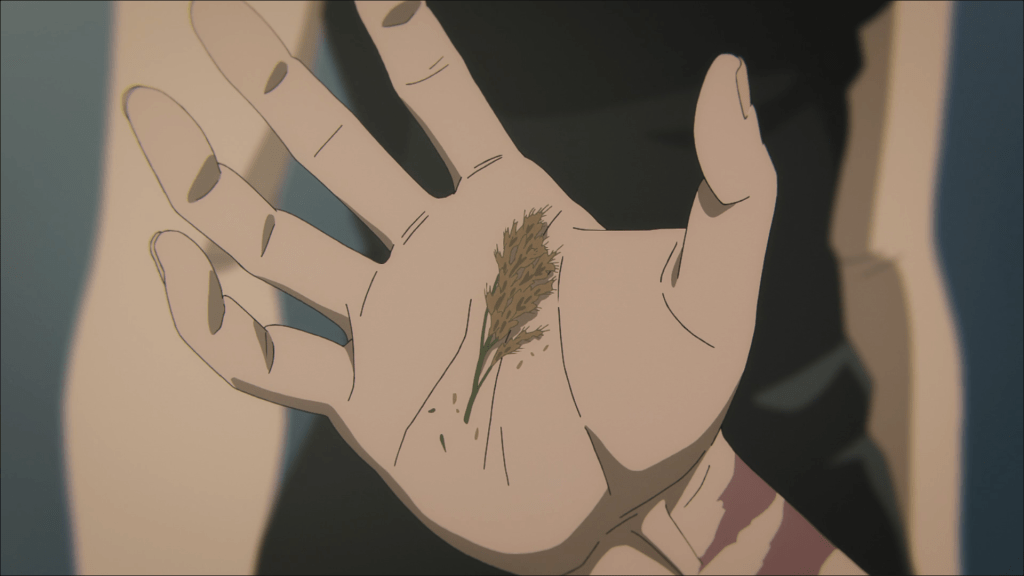

It even made me feel sympathy for Maki’s sister, Mai, who, up until this episode, I loathed for the way she treated Nobara. Maki and Mai were inseparable in their youth and found solace in each other’s company under the shadow of an unforgiving family. However, Maki couldn’t stand the mistreatment she received, so she left to strike out on her own, intent on becoming a big-shot sorcerer to spite her family, with aspirations of taking over the Zenin clan and creating a place where Mai could be happy. The most tragic part, then, was that by doing so, she left Mai alone, something she considered a betrayal, and which left her bitter.

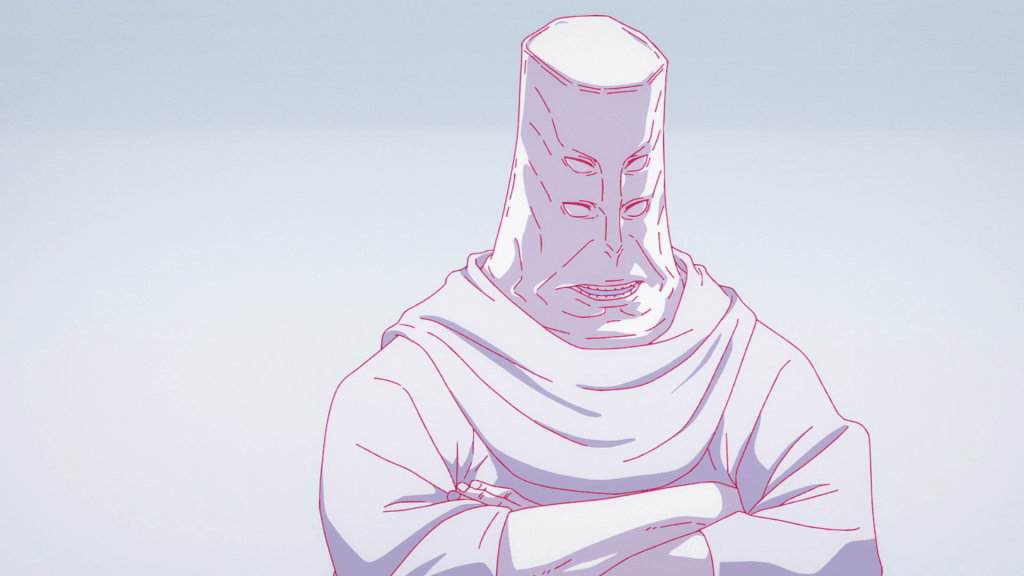

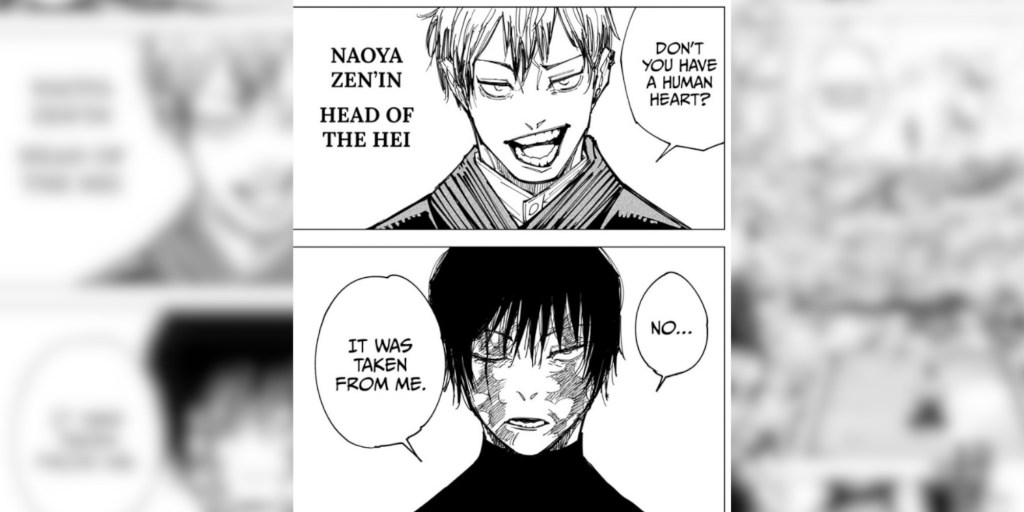

Since the beginning, we’ve known the Zenin clan as a bunch of big-shot, traditionalist, misogynistic assholes. Every new character from the clan introduced only reinforces this notion, from the drunkard head of the family, Naobito, to his shithead son Naoya, and so on. We’ve been given further insight into their nasty reputation through Megumi’s backstory, his unfortunately badass absentee father, Toji, and Satoru Gojo’s blatant warning to a young Megumi about the clan. While not technically the main antagonists, the Zenin are appropriately built up as a menace. The only real difference between Season 3 and what came before was that previously, their presence was like a bad memory, but now, they are a barrier between our protagonists and the goals they’re trying to reach. And frankly, this was inevitable.

A lot happened in Season 2, not just within the text but in my mind as I was witnessing it week by week, and one of the themes that became blindingly apparent was one of systemic failure. Suguru Geto’s descent into villainy is not insular; it’s a reaction to the ceaseless consumption of life by the career of “jujutsu sorcerer”. Geto has to wrestle with the death of Riko Amanai, only to find out that there was apparently another Star Platinum Vessel, so to the higher-ups, it’s no big deal that she died. And that’s just the beginning. Throughout Season 2, the “adults” of Jujutsu Kaisen are morally ambiguous at best, and woefully corrupt at worst.

Maki’s Role In Jujutsu Kaisen’s Larger Message

If we look at jujutsu society not merely as a fantasy world hidden beneath our own, but rather as a microcosm of our real world, then the direction of the story, post-Shibuya, is quite clear. To my mind, it’s about a new generation facing an uncertain future that will not wait for them to mature before putting them through hell. In turn, it’s about these same youths taking charge to fix what the previous generations broke, with the help of the adults who still give a shit. In that sense, it’s very similar to the way My Hero Academia‘s themes developed, albeit over a shorter timeframe by comparison, and that’s not too surprising. These kinds of themes resonate with younger audiences, but unfortunately, they’re also becoming distressingly more relevant.

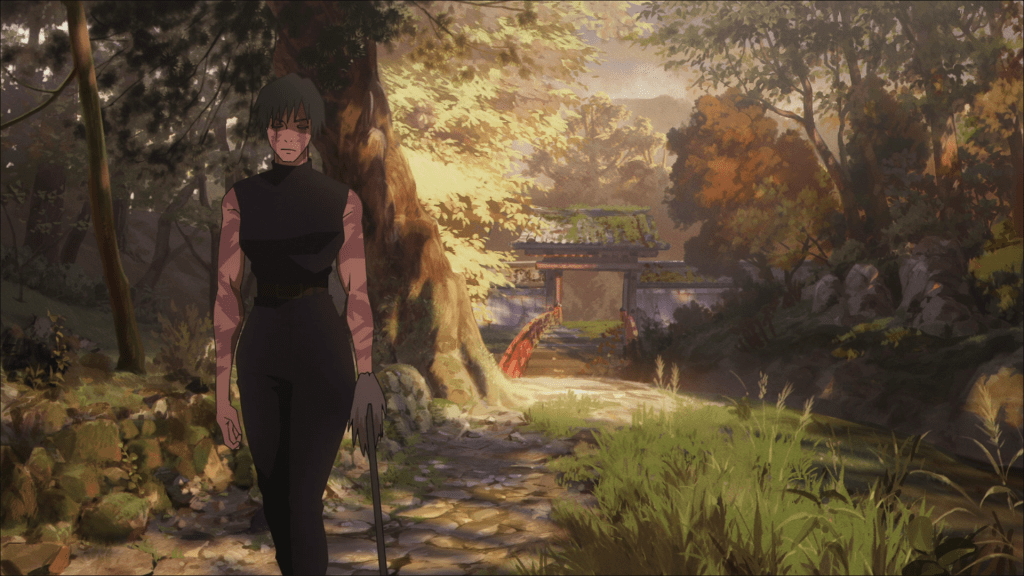

This is another reason why Maki only had bigger places to go in this story. She’s already awesome, but she’s also inspiring in a way that ties nicely into the kind of story I’ve described above. If anyone understands the systemic flaws here, it’s her, and from the beginning, it was clear that confronting the Zenin clan was inevitable. And the thing is, even with all the confidence that made her so endearing and the combat prowess that made her formidable, her greatest aspirations were always going to be a behemoth. That’s because, compared to her family, she’s still a weakling. Or at least, she was.

My Favorite Part of Jujutsu Kaisen

Episode 51, titled “Perfect Preparation,” is not just a homecoming but a reckoning between Maki and the Zenin clan; an unforgettable spectacle with huge implications for this story going forward. It’s named after the five-chapter story (four parts and one epilogue) of the same name from the manga, although its namesake is only a third of an encompassing 15-chapter arc. While Season 3’s titular Culling Game is billed as the main attraction, two smaller arcs precede it: “Itadori’s Extermination” and “Perfect Preparation”. The former (7 chapters) is covered by the very end of Season 2, and the first episode and a half of Season 3. Meanwhile, Perfect Preparation is adapted in episodes 49, 50, 51, and probably the next episode or two.

I knew this particular story was going to be adapted well. Season 2 of Jujutsu Kaisen alone made Shoto Goshozono one of my new favorite directors, and what his team has been able to accomplish under the questionable conditions of the industry’s biggest studio is nothing short of generational. There was no doubt in my mind that they would create something as cathartic in animation as it was in the manga, at a time when Gege Akutami wasn’t in the best of health, something reflected in the raw, emotion-drenched artwork. I knew it would be great… but I gotta be real, I didn’t think they’d make something quite as great as this.

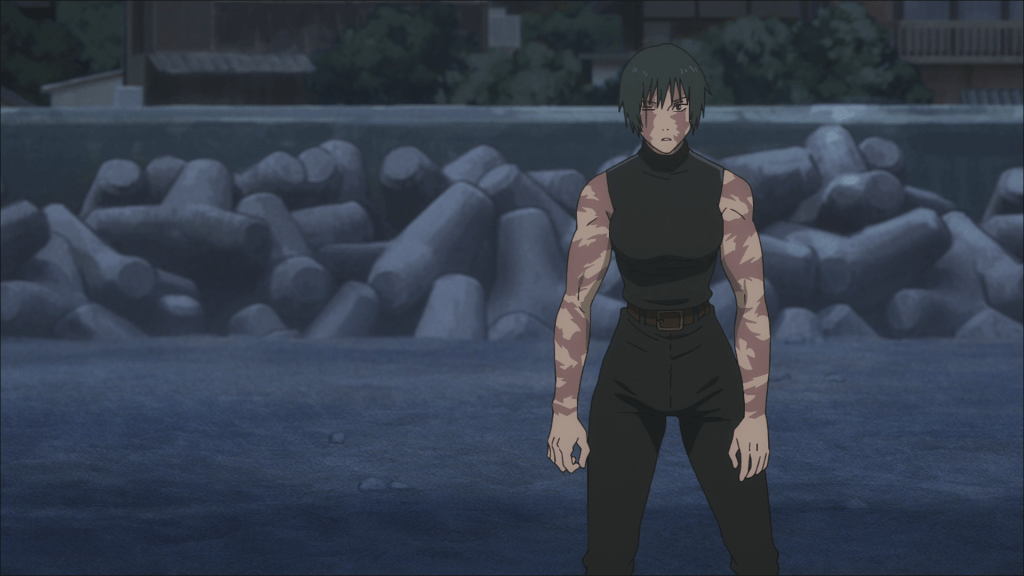

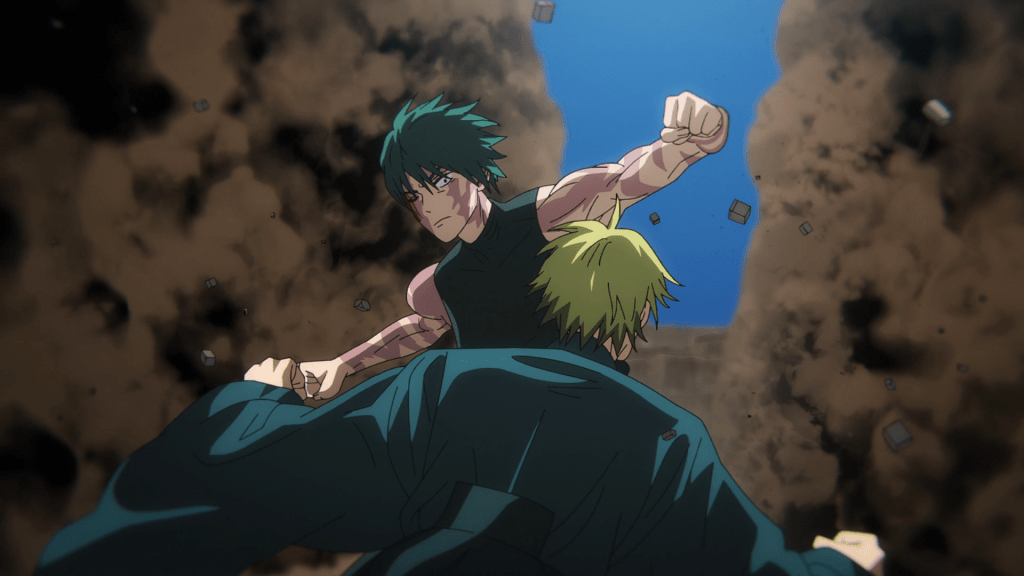

For starters, I didn’t think they’d cover so much ground in a single episode. At the very least, I assumed that the beginning of the story would come at the end of a previous episode; I figured Maki killing Ogi in a single blow would be the cliffhanger leading into the main event. Instead, the episode covers everything from the moment Maki returns home to the moment she leaves it in ruins, and the 28-minute runtime assuages any concern about a single second being wasted, or worse, that it would feel rushed. That is, if you even noticed the runtime, which I didn’t until a day later on my second watch. I was too busy giggling with glee.

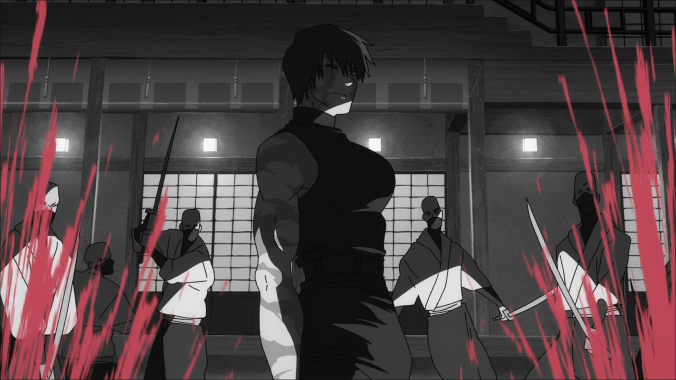

A Love Letter to Tarantino

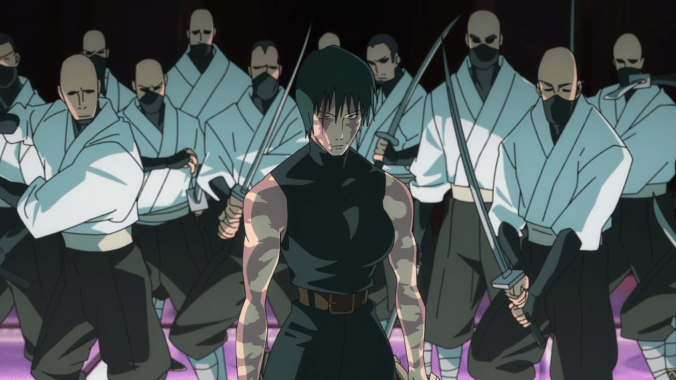

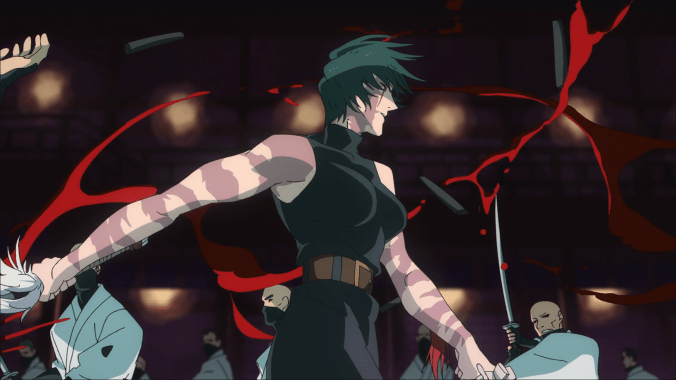

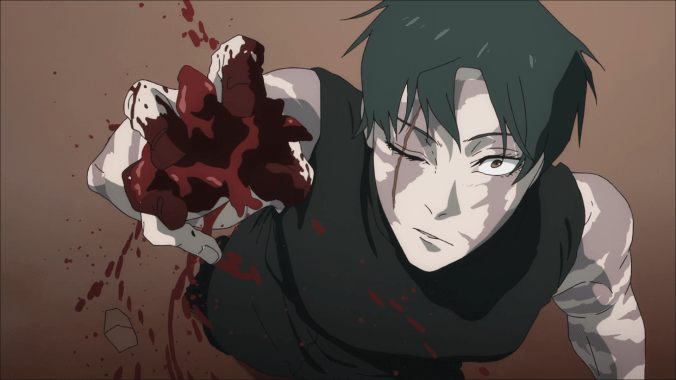

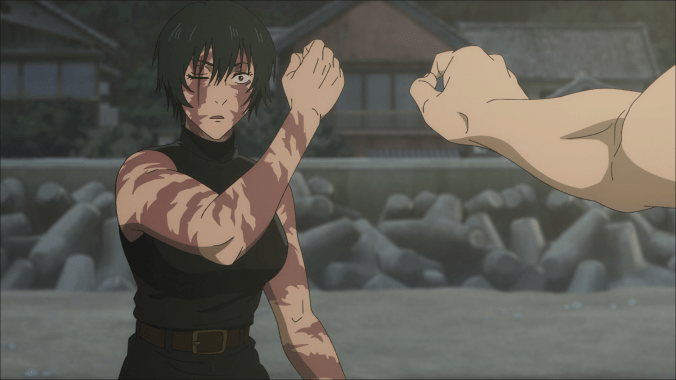

The second thing to surprise me was the tone of it all, at least in the latter half. When I read the manga, I didn’t immediately pick up on the Kill Bill influences during the fight with the Kukuru unit. I was too engrossed in Maki’s revenge, and in my head, I imagined a much darker tone, with an eerier, almost horror-like presentation, as if we were witnessing Carrie in a fresh coat of pig’s blood, merely witnesses to the ensuing rampage. I’ve never been happier to be so wrong. It doesn’t just co-opt the staging of Quentin Tarantino; it captures the vibe of the Crazy 88 battle, and the heart of a revenge story in general, perfectly.

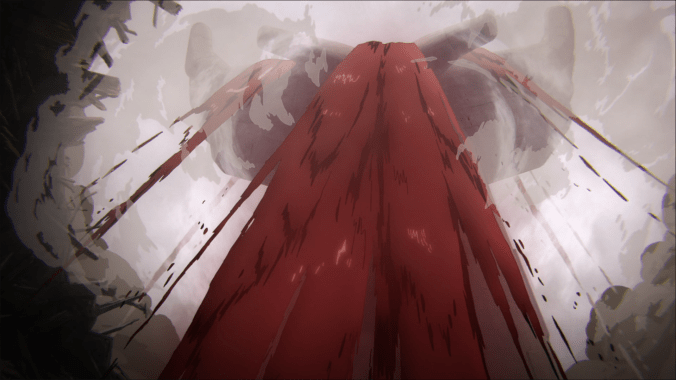

The previous week’s preview was the first clue, with a plucky acoustic guitar straight out of a western. As soon as the Zenin clan raises the alarm, the drums gradually build tension as the Kukuru unit assembles to surround her, until all falls silent. Even the start of the fight is bereft of a score, letting the clashing blades and spurts of blood fill the air, just like in Kill Bill. Soon enough, though, Yoshimasa Terui’s score breaks through again, with jazzy drums, electric guitar, and a blissful, non-lexical “la la la” serenading Maki. It’s cathartic, it’s electric, and it’s just… fun. If Tarantino had wanted the Crazy 88 sequence to be animated, I have no doubt it would have looked – and especially sounded – like this.

Reaching Staggering New Heights

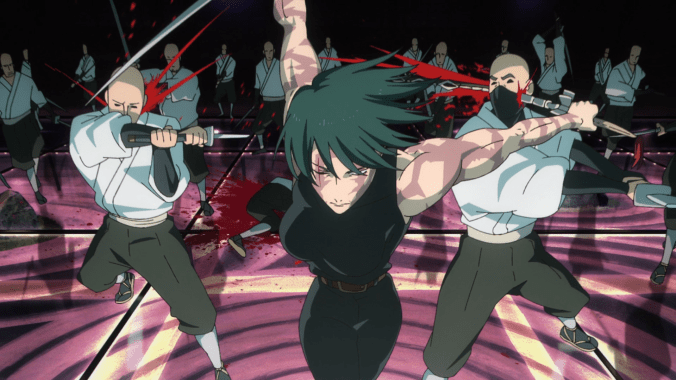

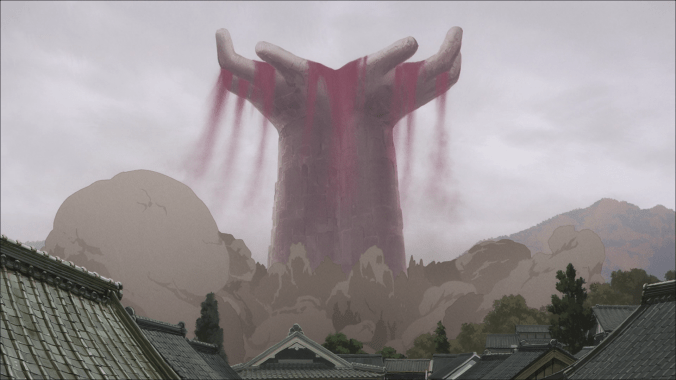

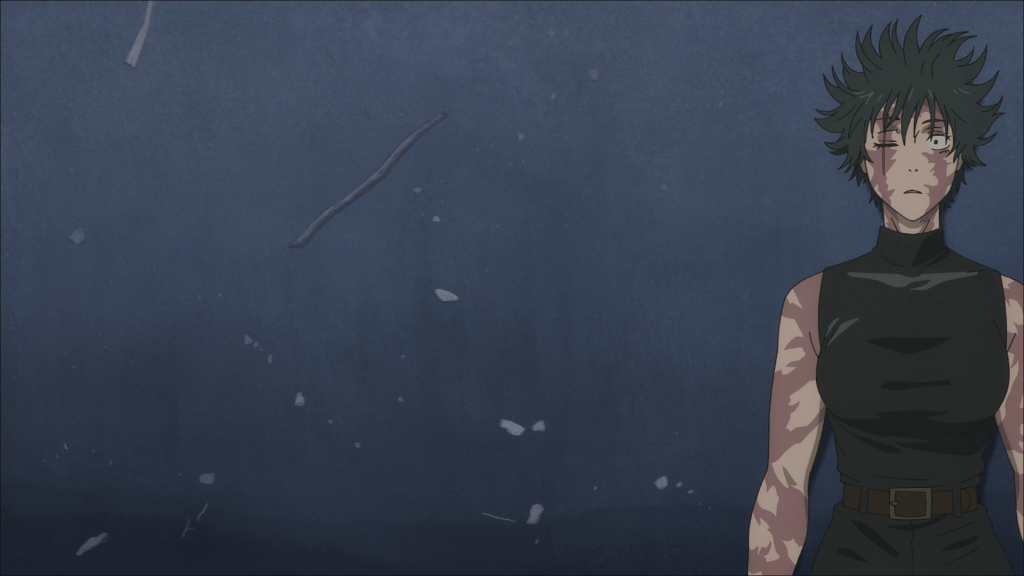

Even after the Kukuru unit is slain – you know, when the action explodes beyond the confines of the building – it never loses that charm and sense of frivolity, which, to me at least, is proof that the similarity to Tarantino isn’t superficial. It demonstrates an understanding on the part of the storytellers as to what makes a revenge story like Kill Bill so unforgettable. So even as the action abandons any association with its filmic inspiration, it carries that tone and those powerful emotions to fuel a climax that never relents. It’s part of the reason why the story can get away with introducing and killing off the Hei in the same episode. We are told that they are the strongest of the Zenin clan, then they hit Maki with everything they have, and then they die. I love it.

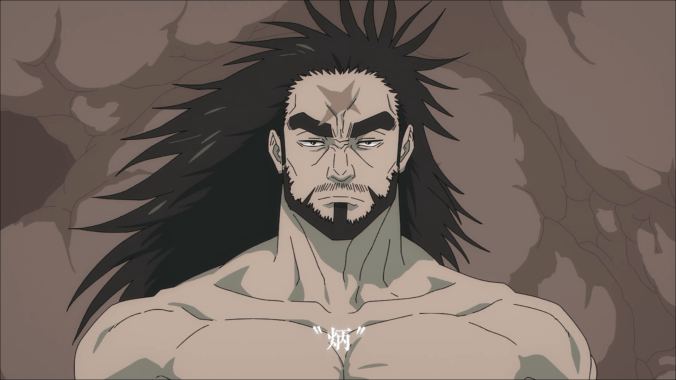

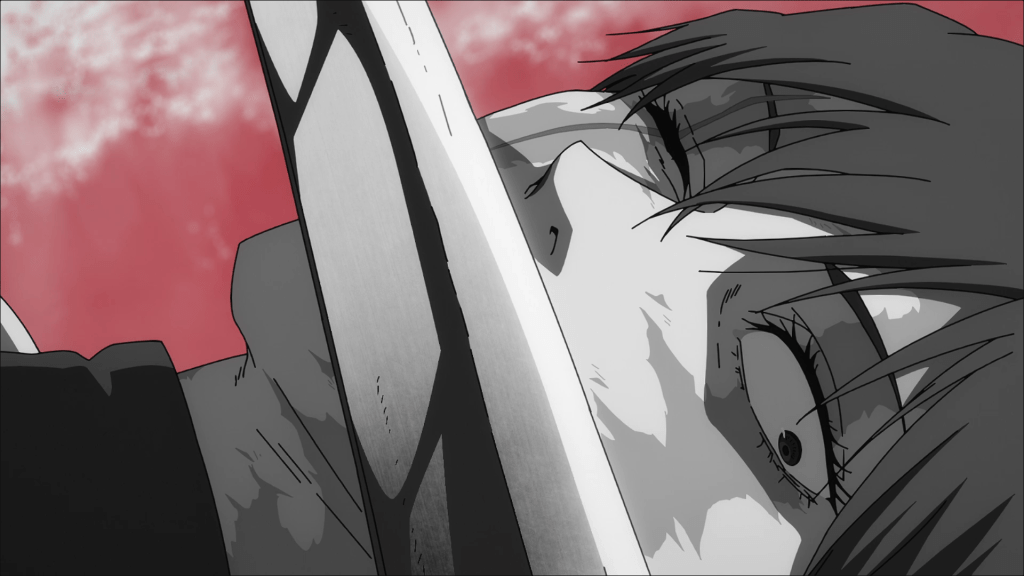

From beginning to end, there was something nostalgic about the art direction in this episode. Sure, there were plenty of modern, “cinematic” stylings to the directing, but just as many shots and cuts that felt like something out of the repertoire of GAINAX in the 2000s or Trigger in the 2010s. Even the color grading and the way that Maki was drawn felt “old-school” in a way I can’t quite put my finger on, but the best I can say is that the artwork scratched a particular itch for me, one that Jujutsu Kaisen has scratched more and more as it’s gone on. God, I haven’t even talked about the Naoya fight yet.

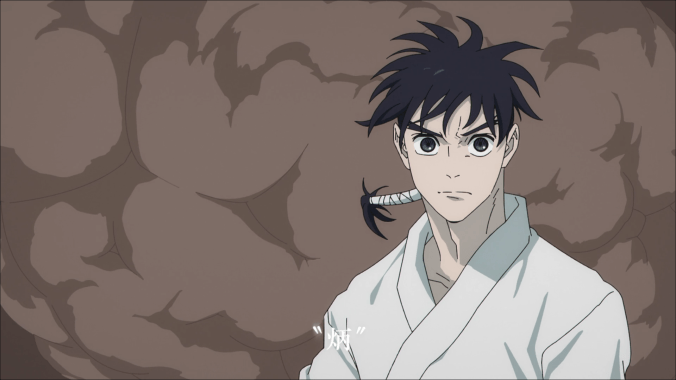

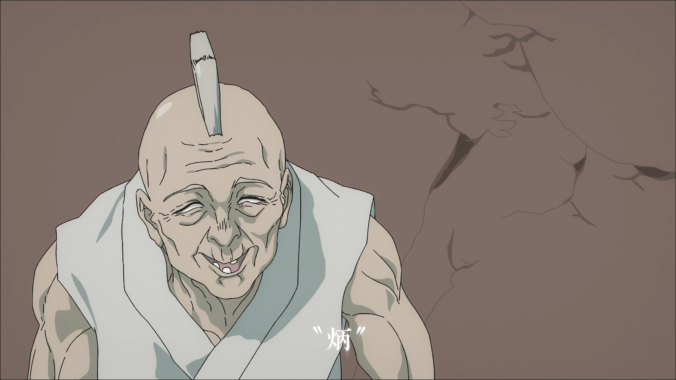

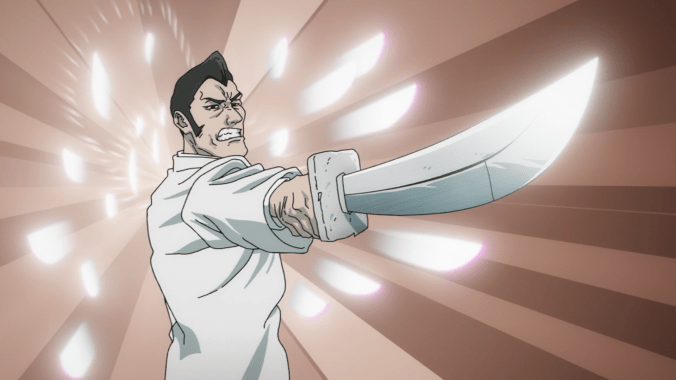

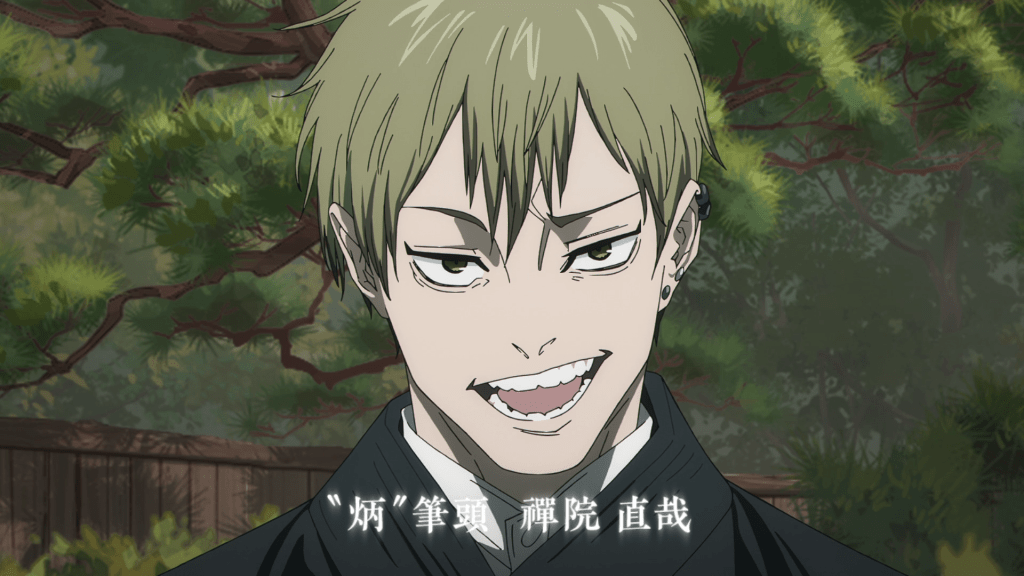

There’s something about characters who show up out of nowhere, make themselves instantly important, and then spectacularly exit the stage (at least for now) that will never get boring for me. Naoya is such a smug piece of shit, but he’s the best kind, because, like any member of the Zenin clan that isn’t Maki or Megumi, his ugliness is packaged in an undeniably alluring charisma and an equally attractive design. Top it all off with a great vocal performance by Kouji Yusa and a really unique cursed technique, and you have the makings of an excellent villain. He’s the perfect asshole to cap off Maki’s world-record speedrun for dismantling the patriarchy. Just when I was convinced the show was gonna save his fight for the next episode, they fit it in perfectly, and captured his cumupence from every angle for good measure.

Coming Down From The High

So far, this is the best episode of the season. I’d go further to call it one of the best episodes of the entire series, of which there continues to be stiff competition with each passing story beat. More than anything, though, I’m so happy that this moment not only lived up to the original chapters that got me so hyped but exceeded them with style. This adaptation is truly a gift that keeps on giving, and I hope I’ve articulated why as colorfully as I’ve expressed my glee with this arc. I want to be fair and balanced, but it’s honestly hard to find anything I would have changed for the better that wasn’t already done splendidly. That’s not to say I haven’t heard criticisms from fellow writers, though. Namely, concerning character writing and the build-up therein.

There’s fair criticism to be made of Jujutsu Kaisen‘s writing; how it establishes, develops, and especially how it ends certain character arcs. That being said, I’m not a fan of the idea that people have to “turn their brain off” to enjoy this episode just because we lack a prolonged investment in certain characters, like Naoya, like the Hei, and so on. I know that critics like myself often assert the “show, don’t tell” rule, but I feel like people forget that the way we “tell” something can make all the difference. It’s why we still utilize narrators, and wouldn’t you know it, Jujutsu Kaisen has Yoshiko Sakakibara, a woman with a phenomenal voice, to narrate the story.

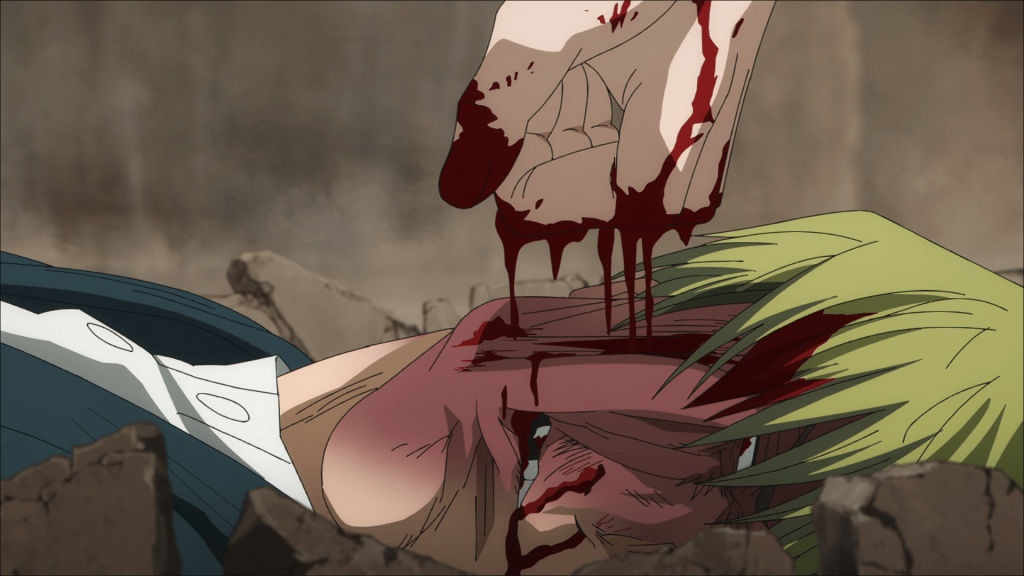

The Shadow of Toji

And for that matter, this episode “shows” the audience plenty. It’s not as if the aesthetic presentation struggles to make the Hei look powerful. The animation is firing on all cylinders, and the character’s powers are easily understood without exposition. Would this episode’s climax be more satisfying if we’d spent an entire season getting to know the Hei? Eh, maybe, but that wasn’t the point of this story. It was to demonstrate just how powerful Maki had become, what she had to lose to attain that power, and – in a karmic sense – how fragile the Zenin clan always was.

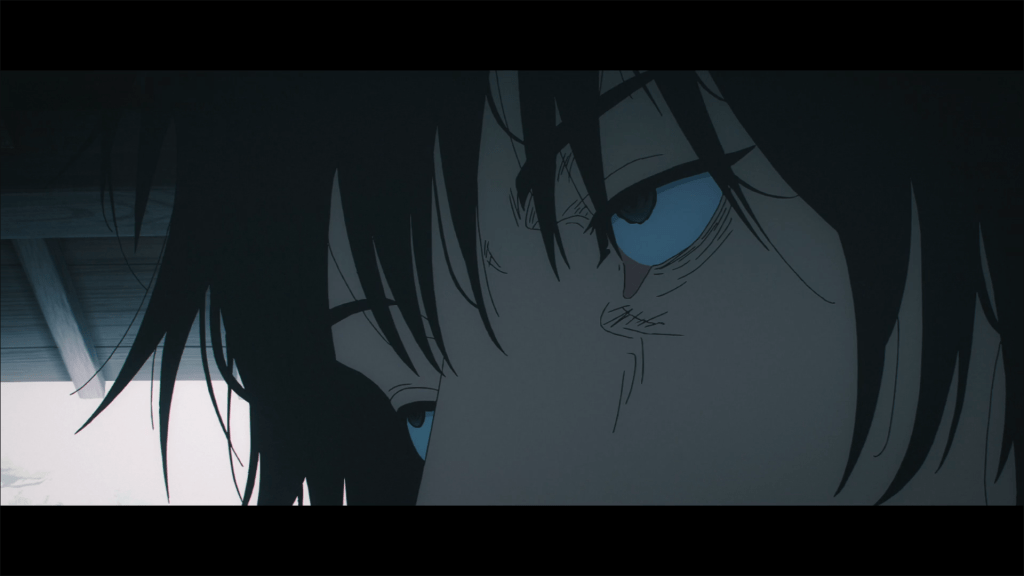

The transformation that Maki undergoes in such a short time is really fascinating, not only because of the tragedy therein, but also in how it manages to give closure to a character who isn’t even there. Toji Fushiguro, Megumi’s sleazebag of a father, was one of the most memorable characters of Season 2 for a multitude of reasons, but the most pivotal here was his heavenly restriction. He and Maki are very similar, but Toji was always more powerful; he didn’t even need glasses to see cursed spirits. If Maki was an exception to Jujutsu Kaisen‘s magic system, then Toji is a contradiction to it. And now Maki has become just like him.

What Killed the Zenins (You Know, Besides Maki)

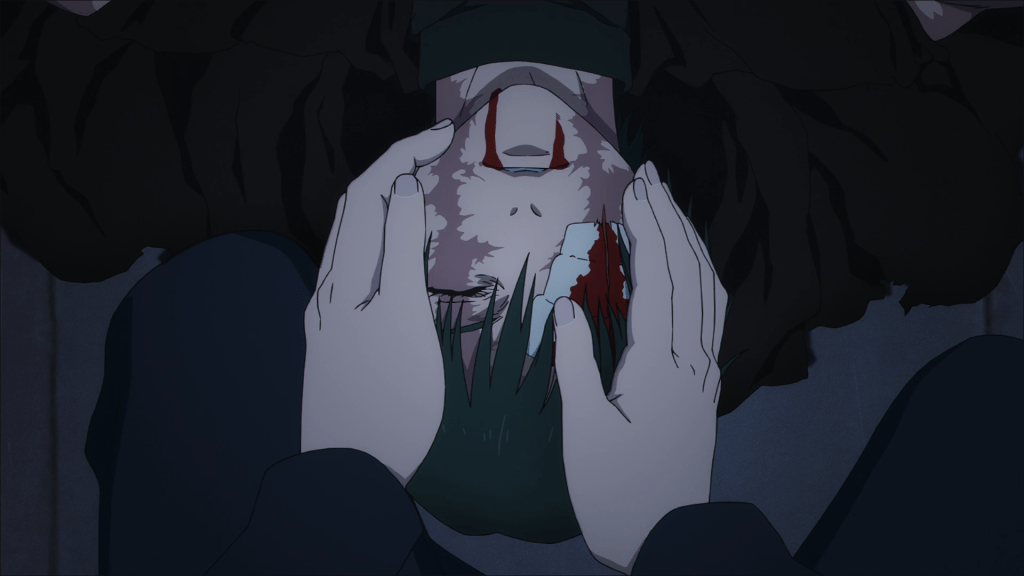

Mai’s decision to die and take the rest of Maki’s cursed energy with her breaks down the remaining barriers between her and her aspiration of succeeding her clan. The only difference is that now, Maki doesn’t care about trying to reform it. Even if she believed she could, she’s lost the only reason she’d want to, and the ensuing rage makes something abundantly clear: Toji could have killed all of these motherfuckers if he put his mind to it. It’s not-so-subtly spelled out later by Ranta of the Hei while Jinichi aurafarms his way toward a quick death against Maki. And that cold reality is why I don’t care that we never got some sort of deep character development for more of the Zenin clan. They’re losers who have always been secretly terrified of being undone by that which contradicts the foundation of their power.

For that very reason, Maki was the perfect person to bring the clan to its knees. It’s not just awesome because she’s a woman fighting back against a sexist power structure that demeaned her and others like her (although that certainly makes it all the more delicious). Maki’s revenge is powerful because her strength, by its very nature, disregards everything that the Zenin clan’s status is based on. It’s like that old quote from Game of Thrones: “power resides where men believe it resides.” Sometimes, the worst thing you can do to an oppressor is make them realize that the power they think they have is meaningless against you… and then maybe like, kill them with a big sword or something – I don’t know.

A Conclusion (& Response)

I had a lot of concerns going into Season 3, partly because of how much I love this story and partly because I remember the reported conditions behind Season 2. The fact that the Shibuya Incident was as good as it was from beginning to the end is a miracle, but it shouldn’t have had to be a miracle, and I feared there may come a time when that magic would wear off. It hasn’t happened yet, though, and so far, I think Goshozono and the team continue to deliver one of the most aesthetically pleasing mainstream shonen series on TV. It’s got good action, sure, but more importantly, it is filled to the brim with great art of all kinds and storytelling that leverages said art to be as engaging as possible, even during exposition.

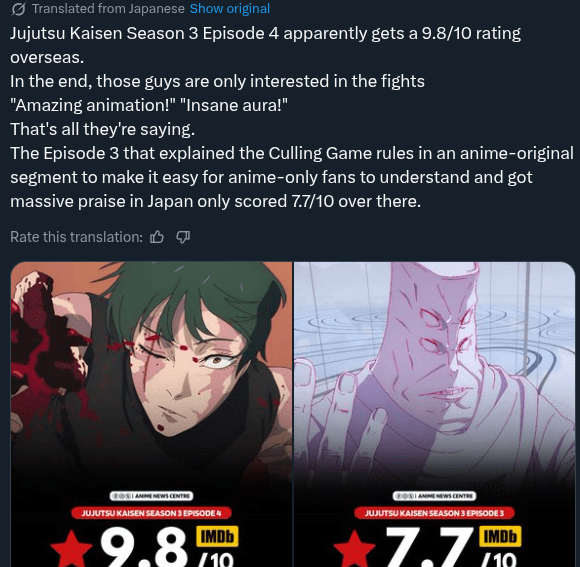

You know, I was really tempted to completely ignore this, but I was made privy to a viral tweet from a Japanese fan who was complaining about the episode scores in Japan versus overseas. In particular, they pointed out how Episode 50 scored a 7.7 on IMDb, whereas Episode 51 earned a 9.8, and accused Western fans of only watching anime for cool fights and aurafarming. Firstly, I’m so glad I stopped using Twitter, because I just know I’d get discourse as heated as this – if not worse – at a staggering volume. Secondly, I don’t think this is a great take. They’re making a lot of assumptions about how genuinely people are engaging with this story and really dismissing the quality of Episode 51. However, they are right about one thing: Episode 50 deserves a lot more praise.

In Defense of A Bad Take

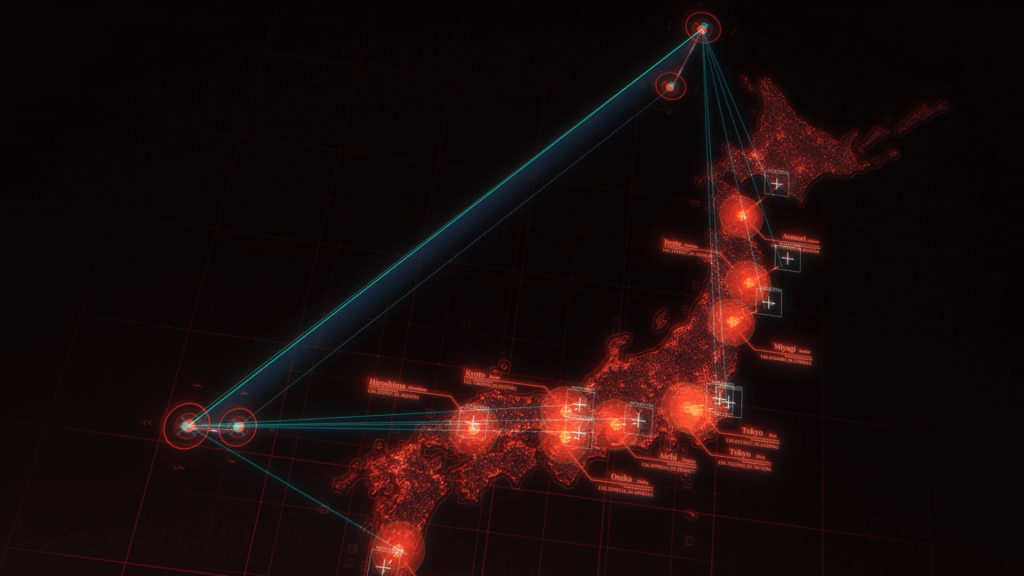

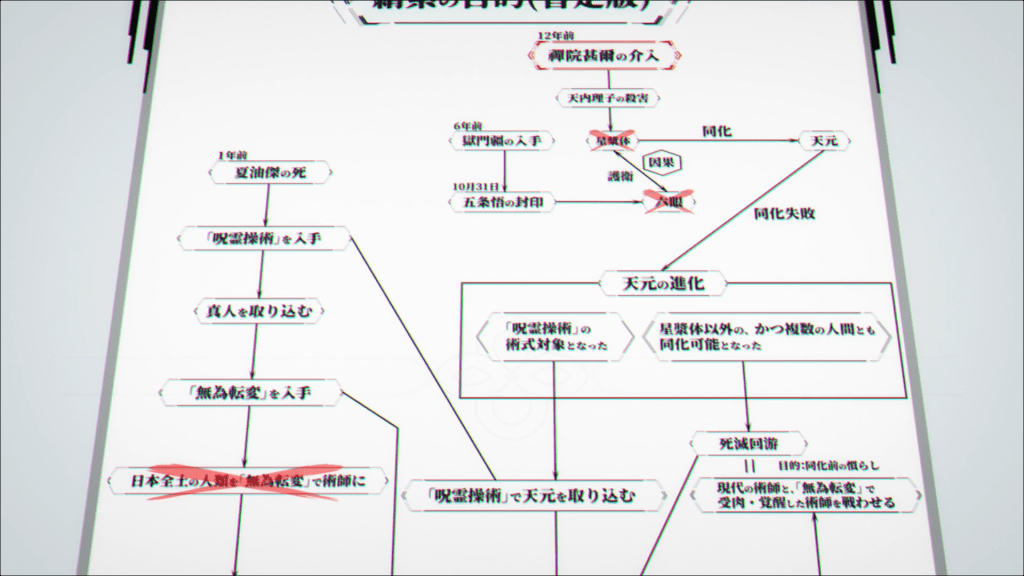

Let’s be real, from the Culling Game onward, Jujutsu Kaisen can get pretty confusing, whether it’s how some cursed techniques work or the myriad ways people can stretch and even break established rules. By the time I was reading the final arc, there were times when the blocks of text explaining what was happening were actively impeding my enjoyment of the finale. We can blame translators and audience attention span all we want, but Gege Akutami’s storytelling is undeniably – and I would argue even charmingly – complex. So the fact that they made an episode all about explaining the Culling Game, and made it this entertaining, is really impressive.

It takes the white void in which the chapters took place originally and uses it as a canvas to lay out the next steps of the story in a way that is super fun and interesting to watch unfold. You might have to pause or rewind once or twice, but compared to a static page that a reader may pore over as long as they need, this episode had to convey a lot of information in motion and did so with excellent adaptive flair. It reminds me of the Monogatari Series, a franchise known for taking already compelling dialogue and matching its charm with visual direction that refuses to let go of your attention.

Why the Take Still Sucks

With all that said, you are talking out of your ass if you think Episode 51 doesn’t deserve the praise, and I can say that because – for once – I read the manga. That, and I also just spent like a whole essay speaking to the charms of this nearly-30-minute masterpiece. Granted, I’ve seen some, like Alina Joan Ito of Tokyo Weekender, point to a cultural divide in the reception to this episode, one that feels very familiar to the divide regarding Season 1 of Chainsaw Man. For those who aren’t aware, the short version is that Japanese audiences were more critical of Chainsaw Man‘s anime because of its stylistic differences compared to the source material.

I don’t want to claim to understand the full scope of the discussion from the Japanese perspective, and I certainly don’t intend to, but I can offer my own perspective as an avid lover of film and animation. When it comes to adaptation, I truly believe that creative liberties are important, whether big or small. You’re taking the work of an artist and feeding it through the minds of other artists, and depending on their talent, that process can either be as reductive as a sieve or as enriching as a boiling pot full of new flavors. Sometimes it will hit, and other times, it will miss. For instance, I liked Chainsaw Man, but after seeing the Reze Arc film, I totally understand why some were underwhelmed with Season 1.

As for Jujutsu Kaisen, I’ve said my piece. Considering the inspirations present in the source material, it’s not unfair to call Episode 51 faithful. I would merely argue that it is also an elevation of the text, one that – for the record – does not demand that I or anyone think any less of the original. I had chills reading the original chapters, and I had even bigger chills watching the madness unfold like I never imagined. Maki Zenin was always one of my favorite characters – this was just the moment it stopped being a competition.

Sources: GameRant, Tokyo Weekender

I loved this episode so much, dude. I hoped to get this post finished before Episode 52 dropped, but the vibes were just off this week. I have so many things I wanna work on, the biggest of which being Draken/Hearth over on Breach Fiction. I wanted to be done with Act 2 by the end of 2025, but that did not happen. Oh well. I’m taking my time with it, and that’s all I can say for right now.

Thank you so much for reading, and as always, stay healthy, stay safe, fuck ICE, and I’ll see you in the next one.