Warning: The following contains minor spoilers for Lazarus, Episodes 1-3, now streaming on MAX.

I love Shinichiro Watanabe’s Cowboy Bebop, but like… in the way that I feel like most people love it. By that I mean I’ve watched it at least once, hold great respect for the artistry apparent in its creation, and I rewatch the three or four episodes I liked the most every once in a blue moon. I actually rewatch the movie more than I do the TV series. Bebop is awesome, but it probably wouldn’t make my top ten (unlike the movie, as I’ve written before).

I compare it loosely to my feelings on Vince Gilligan’s Breaking Bad because, despite it not being among my favorite TV shows, I recognize its patience and strong storytelling and thus have no issues sharing in the fandom’s appraisal of it. It’s possible to not love something while still recognizing its strengths and how it resonated with people. Good art doesn’t need to be for everyone, but I think it’s good (and even necessary) to appreciate widely acclaimed art even when we might not vibe with it.

On that note, it amuses me when I think about Watanabe’s popularity among even the most casual of anime fans, young and old. Without even leaning into it himself, this man has achieved a kind of brand recognition that can sell entire shows just by slapping his name on the tin. Granted, that’s not all that different from how most works from notable directors are marketed, but in Watanabe’s case, it strikes me as particularly impressive because I can easily imagine a universe in which his works are widely considered “mid”.

The Enduring Credibility of Shinichiro Watanabe

When I reflect on my time with any Watanabe show that isn’t Bebop, I recall feeling somewhat lukewarm about most of them, with notable exceptions, of course. Samurai Champloo was fun, but I never found myself loving it, and the ending left me a bit underwhelmed. The same goes for Terror in Resonance. On the other hand, I loved Kids on the Slope, and it’s probably Watanabe’s best show that isn’t Bebop.

I also loved Space Dandy, but I associate that show less with Watanabe and more with its other director, Shingo Natsume (One-Punch Man, Acca-13, Sonny Boy). On the opposite side of the spectrum, Carole & Tuesday lost me late into its first season, though I’m not sure whether or not to blame that on its other director, Motonobu Hori (he also directed Metallic Rouge, which just… ugh). But see what I just did there? See how quick I was to deflect and pass the buck to another creative on the project?

Watanabe is a cool guy with great music taste, a strong fascination with world cultures, a big imagination when it comes to science fiction, and the talent to blend all of those elements into some truly unique stories. But sometimes I get the feeling that we’re all riding the decades-long high brought on by Bebop and forget to view Watanabe objectively, much less the myriad aspects of the productions that hold these newer projects back from being anywhere close to his greatest heights.

It is with that cultural blind spot in mind that I find myself feeling uncertain about Lazarus, a collaboration between Watanabe, Adult Swim, and MAPPA, with action supervision by 87Eleven, the action design and stunt company founded by Chad Stahelski of John Wick fame. This is the latest in a line of ambitious Toonami projects and probably the one with the most riding on it after Ninja Kamui quickly fell off and Uzumaki spiraled down the shitter after one episode.

Adult Swim, The Easy Scapegoat

In my experience, people don’t like to criticize Watanabe too harshly, whereas disgruntled fans are quick to point fingers at Adult Swim when things like this happen. I, too, am guilty of this, because I think there’s an inherent skepticism of attempts by Western production companies to get involved in anime productions. There are many layers to it, but personally, I see Adult Swim’s anime efforts as trying a bit too hard to capture the Toonami “feel” that everyone looks back on so fondly.

So when these original projects end up being “just okay”, it doesn’t exactly inspire a lot of confidence. Ninja Kamui is the perfect example. It felt pretty cheap a lot of the time, compared to even the most mediocre TV anime in any given season. That, plus the story was weak, and the aesthetic presentation, regardless of the quality, straight up abandoned the ninja premise that the show was sold on.

The thing is, though, I can’t confidently say that these flaws lie more heavily with Adult Swim than any member of the production on the Japanese side of things. E&H Productions, the team behind Ninja Kamui, is still a relatively young studio, and regardless of director Sunghoo Park’s reputation (motherfuckin’ Jujutsu Kaisen), that’s not going to magically make a sufficient production pipeline.

I didn’t watch Uzumaki because I heard it was shit, but when it came time to point fingers, I’ve seen way too many people blaming Adult Swim’s Jason DeMarco. He’s a senior producer, Toonami’s co-creator, and the head of all things anime on the network. He has had a long and storied career at the company worthy of respect, but unfortunately, since he’s also the American tied to a bunch of projects that anime fans thought sucked, he’s an easy target.

Why This Is Relevant

I have seen people unironically blame him for Uzumaki‘s failure. When his name pops up, commenters are quick to express caution in the same way that Watanabe’s name inspires optimism. I’m not pointing this out to absolve Adult Swim of all blame for any production fuck-ups, nor am I suggesting that the solution should be to blame Watanabe instead.

What I am saying is that anime, like most audio/visual art and entertainment, is a collaborative process where any number of factors could drag down the final product. Blaming one “side”/person isn’t going to get to the root of the problem, much less contribute to the kind of constructive discourse that yields better art. With all this in mind, this post is going to discuss why I am keeping my expectations low for Lazarus despite – and even because of – Watanabe’s previous works.

What Is Lazarus, and Should You Care?

Lazarus is set in the year 2052, years after a renowned scientist known as Dr. Skinner developed Hapna, a miraculous cure-all painkiller with no side effects. It brought about peace and prosperity, yet after the drug’s emergence, Skinner vanished, only to appear years later with terrible news. Hapna was designed to mutate over time, killing anyone who took it. Skinner has the cure, but humanity has to find him first.

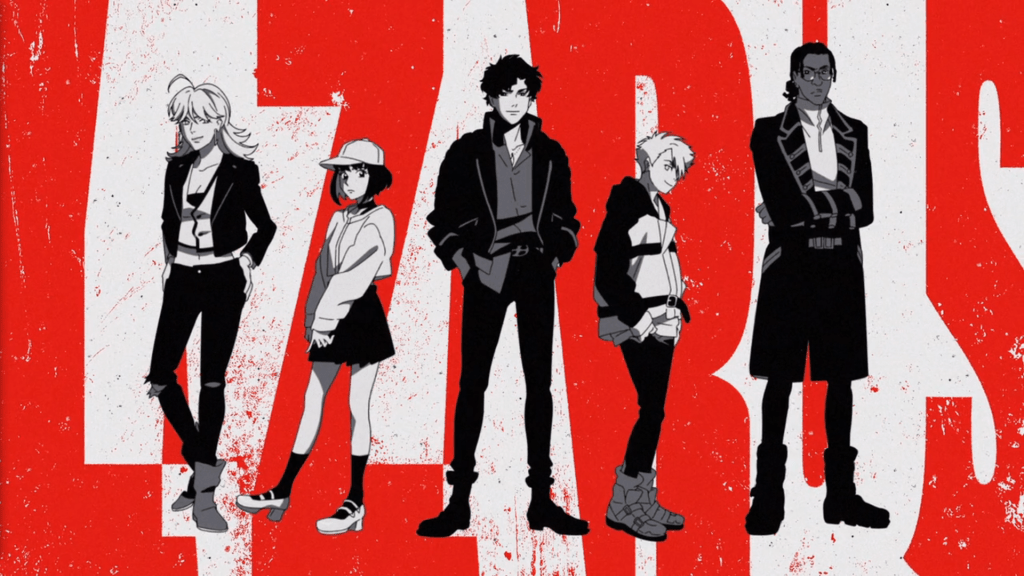

Now, there are only 30 days left to save the world. Enter, Lazarus, a team of five operatives assembled from across the globe to track down Skinner and the cure. Led by a woman named Hersch, the team consists of Doug, Christine (or just Chris), Eleina, Leland, and the leading man, Axel. Judging by the original synopsis, I always assumed that most of the team was there willingly and that Axel was the exception. Instead, it’s more of a Suicide Squad scenario, with everyone wearing weaponized wristbands to track them and keep them from running away.

First off, I like the show’s opening, and I don’t just mean the title sequence above. Both of the episodes that have aired so far begin with this really pretty montage filled with religious imagery, human revelry, war, death, and against it all, Skinner pleading with the world, spinning a dreidel, and watching intently where it will land. In the premiere, Doug narrated this scene, and I assumed this might be a recurring cold open to sum up the premise, kinda like Avatar: The Last Airbender‘s opening.

While I wasn’t technically wrong, it seems like each episode will have a new character narrating this sequence, because in the next episode, Leland takes over. Rather than just repeating the same exposition, his account expands on it by offering insight into how his generation took advantage of Hapna as a recreational drug. Then, Chris narrates Episode 3’s intro, where she discusses how she took Hapna because it seemed like a cure to the suffering that seemed like a prerequisite to just being alive. Yet even then, she suspected that it was too good to be true.

These monologues are a nice touch, especially because outside of these intros, I still don’t know too much about these characters beyond their utility within action scenes. Chris is the firearms expert, Leland is a drone operator, Eleina is a hacker, Doug is the straight-laced strategist, and Axel is the charismatic, agile powerhouse.

They’re all pretty likable, and Akemi Hayashi’s character designs are unbelievably stylish, befitting Watanabe’s storytelling, but as of right now, there’s not much to be said about them. The Suicide Squad framing, and consequently the mystery of why everyone is there, might have actually hurt the foundational character writing.

A Few Questions…

Altogether, Lazarus has an undeniably enticing premise, even if it gets a bit dumb once you think about it for more than a few seconds. Even if you suspend your disbelief that the pharmaceutical industry would have allowed something like Hapna on the market, you’re faced with more questions, such as…

- How can Hapna’s deadly side-effect have such a predictable – albeit broad – onset period?

- Considering Episode 2 reveals that Hapna could serve as a recreational drug, couldn’t the volume of consumption affect the time before mutation?

- How would governments verify the threat posed by Hapna?

- Whether or not they can verify the threat, why would governments and the populace be so quick to believe it (COVID proved that stupid people love to ignore danger, and that was AFTER people started dying)?

- Assuming that Lazarus was formed precisely for this incident, how long before Skinner’s public message did the NSA know about it? Because judging by Episode 1, most of the team was already somewhat acquainted.

- If the team was already assembled (sans Axel) before Episode 1, why were Eleina and Chris so shocked by Skinner’s message?

Look, I’m not trying to be a bitch. I can play along with a fun premise – this isn’t CinemaSins. The issue isn’t even necessarily the lack of answers to these questions, some of which are conceits necessary for the story to exist (like Hapna’s unprecedentedly delayed mutation). It’s more of an issue that I felt compelled to ask them in the first place. My curiosity is not born of a wealth of intrigue but rather a lack of investment; Lazarus doesn’t do the best job of selling the stakes of its conflict.

Lazarus Has a Tone Problem

Since each episode ends by showing the number of days remaining, we know that only a single day has transpired by the end of the premiere. Naturally, this means that the response to humanity’s impending doom is an active, developing crisis. Within Episode 1, we are shown footage of riots, packed hospitals, panicked press briefings, and a late-night interview with an anime knockoff of David Letterman.

But these moments are brief and, at least compared to the aesthetic presentation in the rest of the episode, kinda the bare minimum. Even going into Episode 2, I don’t feel like the world is ending because I can’t see the despair in its inhabitants, and what I do see doesn’t carry a lot of emotional weight. If anything, Lazarus prefers to make light of the coming apocalypse.

This show has a sense of humor, and it would be wrong to discount that immediately. Cowboy Bebop could be funny and heartbreaking in equal measure, but then again, that show was also far more episodic, and its central premise was far less dire. Overall, Bebop leaned heavier on comedy throughout, reserving its emotional gutpunches for when the viewer’s guard was lowered.

I don’t want to keep comparing Lazarus to Bebop and rob the new show of its own identity, but I guess my point is that there was a place for a tonal dichotomy with a bit more balance. Take Bebop‘s premiere, for instance. It had Spike being wacky and lovable, sure, but it also ended with the powerful and unforgettable death of a character we’d only just met in that episode. And that was just how the show started.

Meanwhile, Lazarus‘ second episode has knockoff-David Letterman interviewing knockoff-Sabrina Carpenter about an album that won’t be released until presumably everyone is dead, and it’s played for laughs. Now, there is an argument to be made that this tonal imbalance is intentional. God knows the real world frequently feels like something out of a satire, so why not play into that absurdity in a sci-fi future that, unfortunately, mirrors our own?

In a show about a scientist dooming humanity because he’s lost faith in it, why not some gallows humor to prove his point? The end credits alone depict the worst-case scenario. Everyone is lying around dead while The Boo Radleys sing a song about life without meaning. Looking at it that way, the tonal divide kinda works, but I have a counterpoint. I don’t think it works because it’s not that funny, and I know comedy is subjective and all, but good delivery is a bit easier to qualify (foreshadowing is a narrative device that yada-yada-)

Anyway, it seems Lazarus wanted to prioritize its main characters over vignettes of the world’s collective existential dread. That’s understandable, but in that case, we need to know what they stand to lose. Obviously, their lives are at stake, but how do they feel about that? Is Eleina afraid? Does Chris have loved ones? Does Axel have a dream that he has no choice but to mourn? And would he take that lying down?

These are the questions I find myself asking. But for the sake of variety, why don’t we examine the biggest reason you might not care about a single one of those questions?

Why You Will Want to Love Lazarus

Episode 1 of Lazarus has two objectives: introducing the threat facing humanity, and undercutting that threat through the introduction of our eclectic team of heroes. As we’ve covered, Lazarus puts a much greater emphasis on the latter. Hersch visits Axel Gilberto, a convict serving 888 years in jail, and to the best of the viewer’s knowledge, that’s only because he has a hobby of breaking out of prison.

After turning down Hersch’s offer to get him out in exchange for working for her, he demonstrates this very talent of his in a spectacular prison break. Lazarus really puts its best foot forward on an action front, as one would expect from a season premiere, to say nothing of a production headlined by talents like Watanabe and Stahelski. The jazzy score by Kamasi Washington fills the drab prison with a sense of life and freedom, antithetical and long-forgotten in its darkest shadows.

It’s a great scene, and it only gets better as the rest of Axel’s soon-to-be teammates work together to nab him after his prison break. The citywide chase across subway platforms and rooftops does a great job of demonstrating each team member’s specialty and how well they work together already. All that’s missing is Axel, and the farther he gets on foot, the more he proves why he’s perfect for the team, even if he’s not much of a team player.

The chase eclipses even the prison break before it, partly because the setting is so much more interesting to look at, and because Axel traverses it as if it were built for him. My favorite scene is when Christine cuts off his escape by firing at the glass railings he’s running toward in what feels like a callback to the first John Wick. The harsh but exciting techno score and the sound design, be it gunshots or clambering across architecture, complement the animation perfectly.

I loved this scene, and there’s a good chance you did too. It’s a marvel to behold and exactly what fans wanted from a show with Watanabe’s name on it. Lazarus seems unbothered about the end of the world, but delighted by the thrill of saving it – a thrill it will excitedly invite the viewer to share in. This is the vehicle by which this show earns the hype that Watanabe and Stahelski’s namesake secured. Also, I may have been down on Lazarus‘ humor before, but if anything, this show is the funniest during its fights.

When Lazarus’ Comedy Works

There’s something very Bebop about how amusingly chaotic Episode 2’s climax is. Upon finding a guy who they suspect could be Skinner, Axel and Chris get caught in the middle of a shootout between Russians and Mexicans while Doug and Leland are caught in their own misunderstanding. More and more people start showing up until it’s clear that what team Lazarus has gotten themselves wrapped up in is a completely unrelated mess.

I especially love how, when the FBI and DEA show up, their cars are very clearly competing to get to the scene so they can exert their authority and contribute to the insanity. It’s a brand of humor expressed through action that feels quintessentially Watanabe. Low key, it reminded me of the scene from Cowboy Bebop: The Movie when the police and the military are racing each other to find the chemical weapon, only for them to have both been duped.

The Aesthetic Heights of Lazarus

A little over a month ago, I wrote about the difference between the English and Japanese trailers for Lazarus and how effective each of them was at building hype. In the process, I posited that Watanabe’s works pull people in, above all, because of their vibe:

Cowboy Bebop wasn’t just cool because it was about bounty hunters in space. It was cool because its music, art, and performances created an atmosphere that sucked people in, right before the script peeled back the layers of its characters to reveal their beating, imperfect, utterly human hearts.

I’m a firm believer that aesthetic is narrative, and to that extent, I don’t blame anyone for being firmly seated for the next several weeks. The action scenes (so far) are great, the music blends different genres without the sounds ever clashing, and the artwork across the board isn’t just pretty, but rather unique. I’m not just talking about the gritty, dingy futurism of its architecture, but how the camera moves through it.

I remember it catching my eye during a scene between Hersch and Abel, the director of the NSA. It’s just a dialog scene that could have easily been static and boring (and it kinda is, for reasons we’ll get into soon), but not only is the background art rather pretty, the camera pans vertically during the scene, flaunting the multiplanar composition. It’s a small touch, but it speaks to a drive to keep the visuals interesting even during the most inconsequential of moments.

On a conceptual level alone, there are a lot of ideas that appeal to the superhero/spy fan in me. The way their base is in an abandoned barbershop under an overpass, the way the interior feels so lived-in, and the way the outside wall opens up to reveal the garage are all super cool. I’m just a sucker for any show where the characters have a secret base in which I can imagine them chilling out or goofing off in their downtime.

Unfortunately, while the metaphorical “vehicle” that Lazarus is running on is a beauty to behold, the fuel meant to push it forward can all too often leave it stalled on the road. I haven’t lied about a single word of praise so far, but despite all of that, I’m not sold on Lazarus, and this is in large part due to the script and the performances, specifically in the English version.

When Aesthetics Aren’t Enough

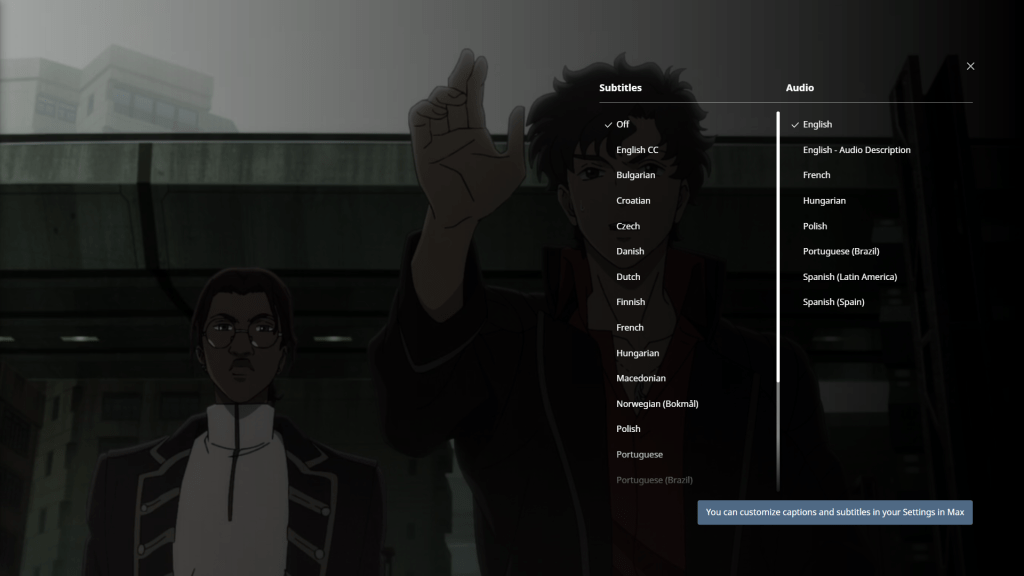

Let’s cut to the chase: it is ridiculous that I can open up MAX, go to Lazarus, boot up the first episode, and listen to it in seven different languages, none of which are Japanese. For perspective, when Ninja Kamui aired, I would watch it the very next day on MAX, with both Japanese and English tracks available. While I am very well aware of the reason for this, it does not make the reason any more sound.

It seems as though Adult Swim was only being generous in the case of Ninja Kamui because the English and Japanese versions aired on the same night. For Lazarus, on the other hand, the Japanese version is airing 30 days after the English version, and thus, MAX only has the English dub (plus six other languages and audio description).

While we’re at it, let me just make it clear for anyone new here. I like English dubs. There are many that I love and even prefer to the Japanese versions. Hell, if you’re reading this with an even passing interest in Shinichiro Watanabe, chances are, you’re a Cowboy Bebop fan, and thus know how legendary that dub is. But I am sad to say that the English dub for Lazarus is just not that great.

Why I’m Not a Fan of the Dub

Perhaps the kindest way of putting it is that it’s underwhelming. It’s by no means terrible. I don’t think the actors are the problem so much as the translation and the directing of the dub. Characters like Hersch and Abel come off a little too stiff, same with Leland and Doug. Even Axel’s delivery, while conveying a fitting cockiness, can come off a little… bored? That’s probably not the right word, but to put it bluntly, I’m not a fan. He’s trying a little too hard to be like Spike Spiegel.

Chris’s actress is probably my favorite because, perhaps by her archetype alone, she’s just a lot livelier, charismatic, and makes the most of the material she’s given. That’s the other thing, though, I don’t think the material they’re given is good. Lazarus‘ script wants to be as fun as its aesthetic, but it comes off as amateurish and, if anything, overwritten. Lines that are redundant or overly edgy – that may have been sold by a stronger vocal direction- end up telling the viewer what could have been – and probably already was – shown.

The Script Shares the Blame

Take the end of the chase in Episode 1, for example. Axel is on the edge, and Doug has him cornered. Axel tips his hat to Doug, explaining how he ended up cornered, which we already gathered because the visual storytelling is competent. There’s some back and forth, then Doug says it’s “the end of the line” before stating the obvious fact that humans can’t fly, painfully foreshadowing that Axel will jump. And that line only serves to elicit a “cooler” line from Axel about how “there’s no fun in being normal”, before he – surprise, surprise – jumps.

Or go even further back, to the beginning of the episode. Doug is in his car, and he asks the onboard AI to play a song. The computer asks what kind of song he wants to hear, and he says, “How about something… with the vibe of a man who sold his soul to the devil… along those lines… that’s what I want to hear.” (That’s the whole line. It’s just… way too many words for one thing).

Music existing diegetically within a story is not an uncommon thing, and in fact, it can work wonders in a story. But Doug is so hyperspecific in spelling out the intended tone of the following scene that it honestly borders on fourth-wall breaking, like the writer was worried the viewer wouldn’t get it. It unintentionally makes the song following this moment – “Dark Will Fall” by Bonobo – kinda hilarious, even though it’s pretty good.

I hope I’m not coming off as overly-analytical or anything. I just legitimately think that this script could do with some trimming to not spell out every little thing. Characters tend to talk in a very unnatural way, especially on the occasion that they reveal important information about themselves. The clip below, from Episode 3, sums up this issue perfectly.

It’s cool to see Watanabe continue his trend of including queer characters, even if just in minor supporting roles, but Jill – a trans woman who the team go to for help – just feels so much less real through the script’s clunky, impersonal prose. To be fair, though, Lucas DeRuyter of Anime News Network made a great point that, considering the damage being done to transfolk and people of color in the real world, maybe beating the audience over the head with such issues is the right call.

Looking at it that way, maybe I just wish the writing had a bit more bite to it if it was going to tackle such large topics. Otherwise, some subtlety goes a long way, and between vocal performances that I’m not crazy about and a script that’s a bit too clichéd for its own good, the aforementioned issues with the premise and my investment in it begin to creep back in, aesthetic strengths be damned.

DeRuyter’s piece for ANN mentioned that the dub gets better around Episode 3 because it seems like the actors have settled into their roles. I actually agree, but this isn’t some early access Steam game; it’s a finished product being aired on TV. The ADR director(s) should be taking the time to get the best out of these actors from the start, or else a critical part of the storytelling is paying the price.

Would the Japanese Version Have Been Better?

For the record, I don’t fully believe that the Japanese version would magically make the script better. Assuming that the English version is at least 90% faithful to the original script, there’s still gonna be problems. However, just as better vocal direction may have softened the blow in the dub, the Japanese performances might have made this script work. And can I be completely transparent? Fuck, I really just wanted to hear Mamoru Miyano as Axel.

No disrespect to Jack Stansbury. It’s just… I pay for my streaming services, or at least most of them (I share the ones I don’t with others). I like having options. I shouldn’t have to wait 30 days to hear a performance by one of the best voice actors in anime. Same with Maaya Uchida or Akio Otsuka. I’m not a native Japanese speaker and therefore am objectively not an adequate authority on “good” acting in that language. I just think Japanese sounds really cool.

Why Lazarus Probably Won’t Be Amazing (But Still Cool)

Earlier, I cited Lucas DeRuyter of ANN, and I actually got more excited for what’s to come after reading his review of the first five episodes. While I may have been underwhelmed by the world-building previously, it seems the story is only going to expand its scope further in the coming weeks. In particular, I’m interested to see how the show handles topics like wealth disparity and sexism. That being said, I’m still going to keep my expectations low.

The most interesting plot threads and themes aren’t going to mean much if the script and character dialog can’t weave them in a manner that takes advantage of the aesthetic strengths rather than bogging them down. After previous Toonami projects, you might be thinking that my apprehension is related, and it would be a lie to say it’s not. I still remember reviewing Ninja Kamui back at Game Rant and slowly realizing the diminishing returns I’d be subject to week after week.

However, to Lazarus‘ credit, this production is already way more promising. It’s not a new or unproven animation studio at the helm like Ninja Kamui or some Frankenstein of outsourced animation work like Uzumaki. It’s MAPPA, and say what you will about MAPPA, but they get results. Furthermore, the aesthetic isn’t some weak pastiche of better art direction that occasionally looks cool. It’s Shinichiro Watanabe. Whether his works hit or miss, they will always look cool.

In fact, Episode 3 gave me more hope than either of the two episodes prior, based solely on how consistently the presentation has managed to keep up with the demand for cool action. Putting aside the somewhat controversial depiction of Istanbul, which, from what I can tell, Turkish fans haven’t been too pleased with, the chase through the streets is unbelievable. It’s a blend of action and humor on a level of fun comparable to the films of Jackie Chan (and in that it’s even more Bebop-coded).

My Predictions Going Forward

I think it’s safe to expect the aesthetic presentation to carry the narrative, especially when it comes to informing the characters through action. There’s still that big nightclub fight from all the trailers to look forward to, and I’m still hopeful that I can come to love these characters as much as I have been passively entertained observing them.

I’m most curious about how the themes will take form by the end, and this is where I really have to manage expectations. From what I’ve seen and what I’ve read is on the horizon, Lazarus is sending its characters on a mission to save the world while consistently pitting them against its worst flaws. By the time they find Skinner, what might all that culminate in? What if that end credits sequence isn’t just a worst-case scenario, but blatant foreshadowing?

There are countless action stories predicated on the evils of what humanity has done to its world, typically articulated by villains despite the real-world threats of climate change. It’s so ubiquitous that it’s become cliche unless a script is particularly smart or its treatment is exquisitely human and sentimental. In the best cases, Humanity’s continued existence is assured by the end and validated through heartfelt prose about our nature and the complex privilege of just being alive.

Such endings exist because the audience is human, and ideally, we’d like to continue being alive. Furthermore, stories that touch upon the complexities of existence through perspective, conflict, forgiveness, and all-around rich emotionality can be incredibly sobering to those who engage with an open mind/heart. Michael Mann’s Heat is a prime example. It’s one of my favorite films of all time, and one that, beyond its cops-and-robbers setup, makes me feel deeply sentimental about just… being alive.

But like… is that the ending we deserve? I know it’s the ending I want, but there’s value in entertaining a less positive outcome. A darker, or simply more ambiguous ending, might be the deciding factor in whether Lazarus really is the “masterpiece” that Watanabe claimed it would be. What if there is no cure? Or, what if there is, but Skinner dies before he can give it to them.

I suppose I’m asking for some kind of fundamental twist, but I’m more intrigued by Lazarus embracing its off-kilter tone and culminating in some dark comedy. Alternatively, in place of humanity dying off, it would be cool if this crisis were a gamble by Skinner to see if humanity was capable of finally confronting itself substantively. Team Lazarus really would be superheroes then; the team that brings humanity back from the brink of death.

Side-note: shout-out to Brett Cardaro of CBR.com for this awesome theory. He compares the premise to the work of real-life psychologist BF Skinner and, combined with an analysis of the religious imagery shown in the series, offers a possibility for how Lazarus will end. I highly recommend giving it a read.

Once again, these are just some of my personal best-case scenarios for this story, and even if it doesn’t manifest in anything like what I’ve described, it could still surprise me with something new. There is one thing that I’m certain will be the case, whether I like it or not, and it’s that Lazarus is going to weed out a lot of fake fans.

More Like Shinichi-woke, Am I Right- *gunshot sound*

You’ll recall I mentioned a trans woman featured in Episode 3, and considering the times, it wouldn’t be a stretch to imagine stupid people bitching about that. They’ll probably say that Watanabe went woke – or more likely that Adult Swim like infected the script with propaganda or some dumb shit like that. I’m just getting in front of it right now to point out that if anyone says this shit while pretending that they’re big fans of Watanabe’s work, they’re lying through their fucking teeth.

Watanabe has always had queer or queer-coded characters/elements in his stories. Maybe not all of them have aged well, but they were implemented earnestly and felt as real and in their right place as anything else comprising the worlds he composed. In an interview with Looper back in 2023, Watanabe had this to say about diversity in his storytelling:

Ever since I saw the 1982 movie “Blade Runner,” I have wanted a future in which lots of ethnicities, races, and genders all lived together. But that sort of future has yet to become reality, so I thought I would at least make it come true in my anime world.

So anyway, trans rights are human rights and fuck you if you disagree.

My Final Thoughts on Lazarus (For Now)

Alas, if Lazarus ends up being mid, I have a sneaking suspicion that people will blame Adult Swim, when it’s just as much par for the course with Watanabe. In recent years, I’ve come to realize that, as much as I respect him as an artist, he’s not as consistent or infallible as some treat him. He has a keen eye for the flavors needed to draw audiences in and command their attention, but without the right collaborators alongside him, it can feel like vital pieces are missing.

That might be the biggest reason I wanted to write this. I want to like Lazarus, and in a lot of ways, I do, because it’s an easy show to like; it’s just not the easiest to love, at least not yet In the beginning, I said that I don’t think we look at Watanabe objectively enough, and that isn’t to say that his highs should be re-evaluated or punched down. Rather, we should just be more mindful of his lows.

I hope the writing improves once the plot starts to introduce more ideas and explore the world, whether it be the innocent lives at stake or the ugliness that brought about Skinner’s wrath. I want to see what kinds of excitement and spectacle Watanabe is still capable of delivering late into such a storied career, and whether this project’s strengths can tower above its weaknesses.

Until then, though, I’m just here for the vibes.

Hey, been a while, hasn’t it? Though not too long now that I think about it. It was just a few months ago that I wrote about Castlevania: Nocturne Season 2, and now I’m back with probably my biggest piece in a few years.

The truth is, my time as a writer at Game Rant recently ended, and now I have way more free time to spend writing for this blog again, in addition to some other stuff I’m working on. Expect to see me pop up on your feed a bit more frequently from here on out.

Also (and I feel like this warrants its own blog post, but I’m not sure how much of a prior reader base still remembers I exist lol), I am a judge for this year’s Crunchyroll Anime Awards. Yeah, surprised the fuck out of me too. All these years of writing, both here and on other sites, really paid off. I’m extremely grateful, and I can’t thank the readers of my blog enough for indulging in my passionate ramblings.

Thank you so much for reading, and as always, I’ll see you next time.